Ellen Angelico Interview: Americana Award-Nominated Guitarist Talks Putting Emotions Into Music, Advocating for a More Inclusive Country Music Community

If you buy into Nashville mythology, you think country stars are born, not made. Many artists point to childhoods of listening to the genre's all-time greats with their grandparents ... hours in the car with their parents, the radio tuned to the local country station ... that country music is their heritage. That’s how they got started.

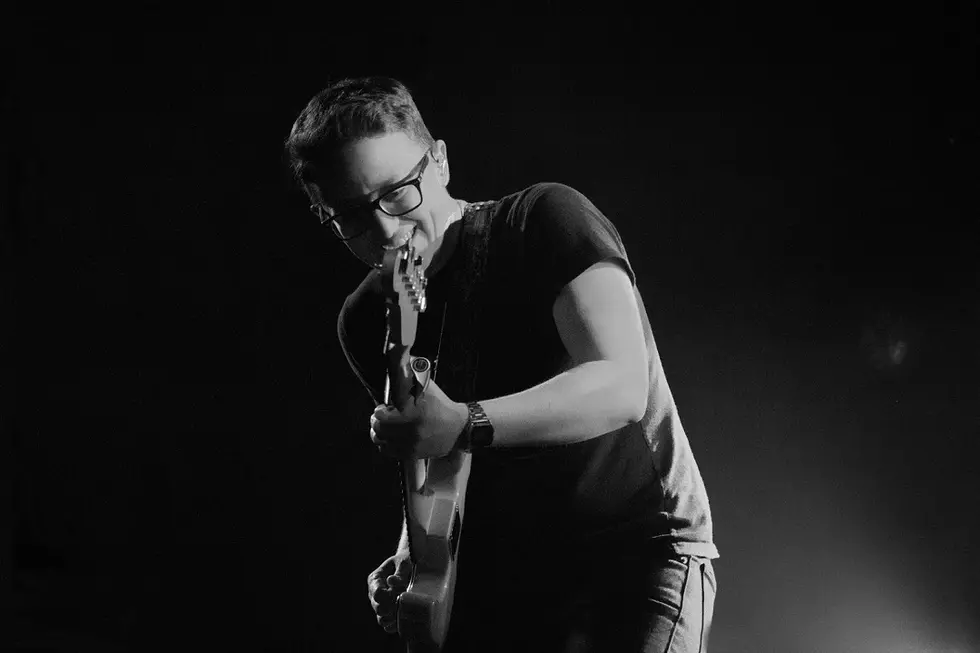

For Ellen Angelico, it was the Canadian children’s singer Raffi. Angelico is the first openly non-binary musician to earn a nomination at the Americana Music Association's annual Honors & Awards ceremony -- and, therefore, the first openly non-binary person to be nominated for any kind of country or roots music-related industry award -- and when she speaks about her inspirations and her commitment to the music and to the future of the country genre, it's easy to see how she received her Instrumentalist of the Year nod.

“We are talking concert tape of "Baby Beluga,"” Angelico (who asked The Boot to use "she/her/hers" pronouns) cracks. "You’re 3-year-old, 4-year-old me, seeing somebody with a guitar, entertaining a large group of people. And I just thought that was what I was supposed to do."

Even as a child, something about Raffi’s performance intrigued her.

“I'm interested in being in charge of people's emotions. And I think there is an element of that in performance," Angelico muses. "And, maybe on some deep, subconscious level, that's what I was gravitating towards: having some power."

Of course, there’s also the reason most people gravitate to a six-string: “Guitars are timeless, cool. Maybe I was just trying to cling to coolness. Because I certainly wasn't exhibiting it in any other area of my life,” she adds with a chuckle.

Angelico has since parlayed that interest -- in power, in coolness, in the mystique of it all -- into international tours with everyone from Uncle Kracker, Americana pop darlings Delta Rae, breakout singer Kyshona and country star Cam, not to mention She's a Rebel, an all-women and non-binary band featuring some of Nashville’s greatest musicians.

Angelico, who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, Ill., describes her childhood as “ideal and idyllic.” There are no musicians in her immediate family, but her parents actively supported her passion for guitar, which she followed to the Berklee College of Music in Boston, Mass.

“I have been blessed and cursed by misplaced confidence in myself,” she admits with a laugh. “The notion of my being one of the few female guitarists, I don't think it really registered to me at the time because of my reckless and wild confidence.”

While at Berklee, Angelico found her niche in the college’s country music ensemble, learning the ins and outs of contemporary country music. Because her friends planned to move to Nashville, and because country music is one of the few genres that has a consistent demand for guitarists, Music City was “an obvious choice.”

After graduation, Angelico “lost a lot of money in an indie rock band for a few years” before joining up with “what essentially was a very successful traveling country cover band.” Soon, she worked her way up to playing in bands, including Shelly Bush's, at the honky-tonks on Nashville’s Lower Broadway -- gigs that educated Angelico’s about country music canon.

“I was lucky to fall into a group of people that were playing enough old-school country music that if they got a request for Taylor Swift or whatever, they would try to pull it out of their butts," she recalls. "That gave me an overview of what I maybe would have missed having not grown up with country music.”

Bush, who died of cancer in 2014, was also a model for Angelico in terms of advocating for representation: “She had a band of all women called Broadband. It was just awesome. They called her the Queen of Broadway," Angelico remembers.

"She was a good-hearted person and a great singer," she adds of Bush. "And I had boobs and a guitar. So I was immediately on every day gig.”

Angelico recalls spending her days cramming popular songs while “slugging it out” in two different sets a night, but after Bush died, she left the honky-tonks in search of other gigs. Like many before her, she parlayed those performances into networking opportunities with songwriters and artists, which is how she found herself with that Uncle Kracker gig.

Of course, it’s not just Angelico’s work ethic that earned her the Americana Instrumentalist of the Year nomination. Kyshona, on whose album Listen Angelico rips some solos, gushes to the Boot, “Ellen Angelico is magic. Period.”

Listening, according to Kyshona, is what makes Angelico special. “Her true gift is her service to the feel and message of a song," the artist explains.

"Ellen is always considerate of how to support not only the groove but the lyric as well. Her bag of references goes deep," Kyshona continues. "She’s an absolute pleasure and joy to work with, keeps you laughing but also on track, and is an amazing cook as well for those long recording days."

Angelico learned of her 2020 Americana Honors & Awards nomination while recording a video with fellow nominee Brittany Howard. The shoot was at Fanny’s House of Music, the legendary woman-owned music shop in East Nashville where Angelico also works.

“I continue to be surprised that I am on anybody's radar! My fame continues to spread farther and wider than I ever wanted. It's an honor to be recognized," she reflects, then takes a long pause, rare in our freewheeling discussion.

“And then I looked around," she continues, "and I saw that I was in an all-white space again.”

As do many others in the country music industry, Angelico sees a need for more accurate representation of country music’s fandom: a demand for the inclusion of women; Black and Indigenous artists, and other artists of color; and queer and trans artists.

“I come from a long line of writers of letters to the editor of the Chicago Tribune,” shares Angelico, proudly holding up a framed newspaper clipping. “I wrote this in high school,” she adds of the letter, a rebuttal of an anti-gay marriage op-ed.

As a teenager, Angelico was not out as gay, nor was she aware that she is gay when she wrote the letter; rather, like many other queer teenagers in the 2000s, she saw herself as a staunch ally.

“I am for gay marriage,” she wrote as a teenager, “because I care about lives that are not mine.”

True to those words, Angelico has joined other marginalized instrumentalists in Nashville to push for more representation -- and more gigs. And now that more artists are staying home and livestreaming, she is seeing some changes.

“I see people trying out folks just because they can -- and because everybody's home," she says. "But I don't see a lot of [long-term] positions opening up."

There is the potential for change, of course. “Like a lot of people, I've learned more about anti-racism and anti-Blackness in the last year than I have in the whole rest of my life," Angelico continues. "And I'm trying to listen to people who know more than I do. And I'm trying to question the all-white spaces that I find myself in, and it's a lot of spaces.”

Country and Americana music, Angelico notes, can only benefit from expanding their perceptions of who gets to sing -- and play -- it.

“I know a lot of talented musicians who are queer musicians, who are Black; I would love to know more musicians who are Indigenous, I would love to know more musicians who are disabled, and just get them into these conversations, because I think that they don't see themselves in country music, and so they go to other parts of the music world. Or they think they can only be artists and not sidemen," she points out. "And the skills that they are acquiring in those other zones of the music industry are applicable in the country music industry.”

For Angelico, it’s not just about helping people land paying gigs -- though she does advocate for other musicians. “It's about getting queer people and BIPOC into the decision-making places: the boards of different governing bodies and trade organizations within the music industry," she says.

"Country music specifically has, like, very clearly invested in white straight people for a long time. And hedged its bets on white straight people for a long time," Angelico continues. "Which is insane, because it's like, there's this whole other market of listeners! By excluding queer people and BIPOC from the conversation, you're excluding the market share, you're making a decision to exclude a market share, you're making a decision to make less money.

"So that's the thing that I just can't wrap my little squirrel head around," she adds. "And that's why I'm so motivated to question the all-white spaces that I find myself in.”

In both her activism and her musicianship, Angelico envisions a fundamentally egalitarian world. “I love songs, I believe in songs," she reflects. "I think the reason that I'm so passionate about learning music and learning it meticulously -- learning it the way that it is on the recordings -- is because I want to support the artist’s vision. I want to support the audience’s vision as well.”

Cam, whom Ellen has worked with extensively, confirms that consideration of others: “She’s a definite student of details and leaves the seemingly requisite 'guitar player ego' outside the room (thank God),” says the "Till There's Nothing Left" singer.

“If you go to see your favorite artists,” Angelico explains, “and they're going to play your favorite song, and there's a guitar lick in there that even subconsciously you may not be aware of, but it's making you feel a certain thing, I am the guardian of that emotion.

“Actually,” she corrects herself abruptly, “I'm like a bridge troll: ‘You shall not pass until you feel this way.’ You shall not pass. I shall not pass as cis-gendered! There's lots of lots of passing going on."

A Brief History of Queer Country Music, From Lavender Country to Orville Peck:

More From TheBoot