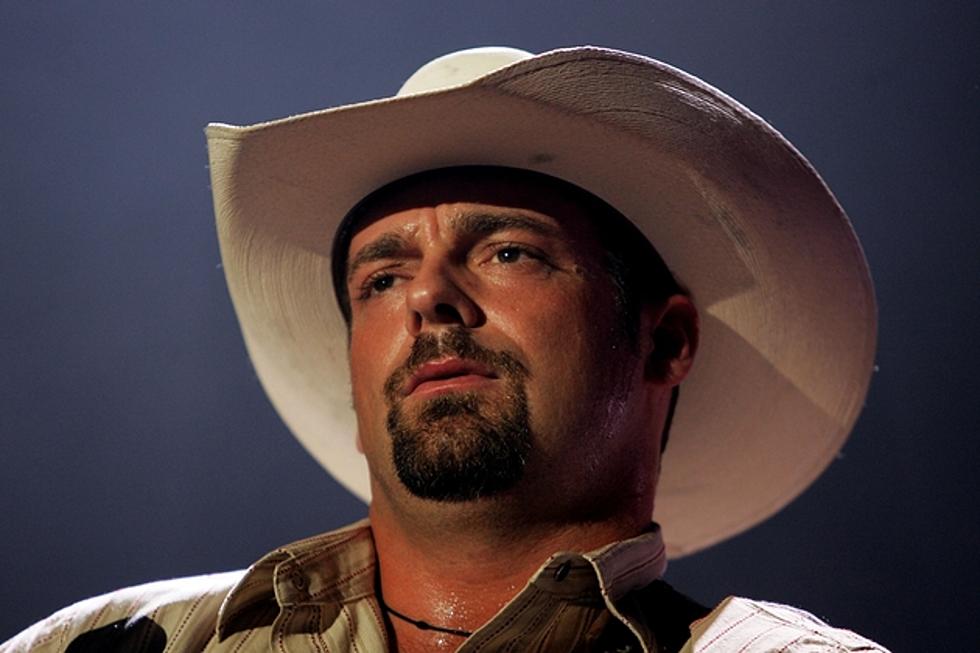

Chris Cagle Interview: ‘Back in the Saddle’ Looks Beyond Troubled Past

Chris Cagle has definitely been through some drama and fought his share of demons over the past decade, with a few of those situations making headlines in the press and eventually starting to nearly overshadow his notable music career. A hitmaker shortly after debuting on the scene 12 years ago on Virgin Records, Chris rocketed up the charts with hits such as "My Love Goes On and On" and "Laredo." But he eventually got snarled up in label changes and business challenges that very nearly derailed the creative train that had taken him to the top. Frustrated and angered by so many things out of his control, the singer began a downward spiral that eventually ended up at a place where often the best creativity happens -- near the bottom. Retreating into himself to find some peace and resolution, Chris went to Oklahoma, built a ranch, and threw himself into training horses and working the land. That sort of medicine is good for the soul and the heart, as he soon found when he met the woman who would become his wife, Kay. The two fell in love and had two daughters, and Chris, who had never stopped performing, soon found himself with a new record deal and a new lease on life. His new album on Bigger Picture, the aptly-titled, Back in the Saddle, out this week, has already yielded one hit, "Got My Country On." The Boot sat down recently to talk with Chris about his eager return to radio after his hiatus, what life is like as the only male in a house full of women, and how he's ready to repaint the landscape of his life with some brighter colors.

You experienced some frustrating and even destructive moments during the years following your time as an artist on Virgin Records. What was your turning point?

I started out this career living the dream. Six months in, the guy who gave me my dream was fired, and they shut down the label. Everybody I poured my heart and soul into, friends and family of mine I was working out on the road for and knowing I was feeding, at Virgin was gone. I was moved to Capitol Records, and my first meeting with the label head he said he never would have signed me. So I asked him to let me go, and he said he couldn't. So I'm out on the road, I'm doing good, I have a girlfriend of three years, we're gonna have a baby, the baby comes out, it's not mine. In the process of that, I find out my manager's duping me, I end up in a lawsuit with him, and I end up medicating myself because I don't want to deal with the sh--. I drank and became an angry person. Finally, one day I said to myself, "You're not even the guy that you can respect, you're not a guy you can look up to. You're not the guy that people fell in love with when you started this, and right now, they're still playing your music. So the best thing for you to do is go away and find that person again. And if you ever get a second chance, make the most of it. If you don't, you've already made it farther than most people told you you ever would." So I bailed, and bottom line is I didn't know if I'd ever have another chance. Then, thankfully, Bigger Picture got involved.

You had been away for a few years when Bigger Picture offered you a deal. Did you have any fears about returning to the intensity and volatility of the business?

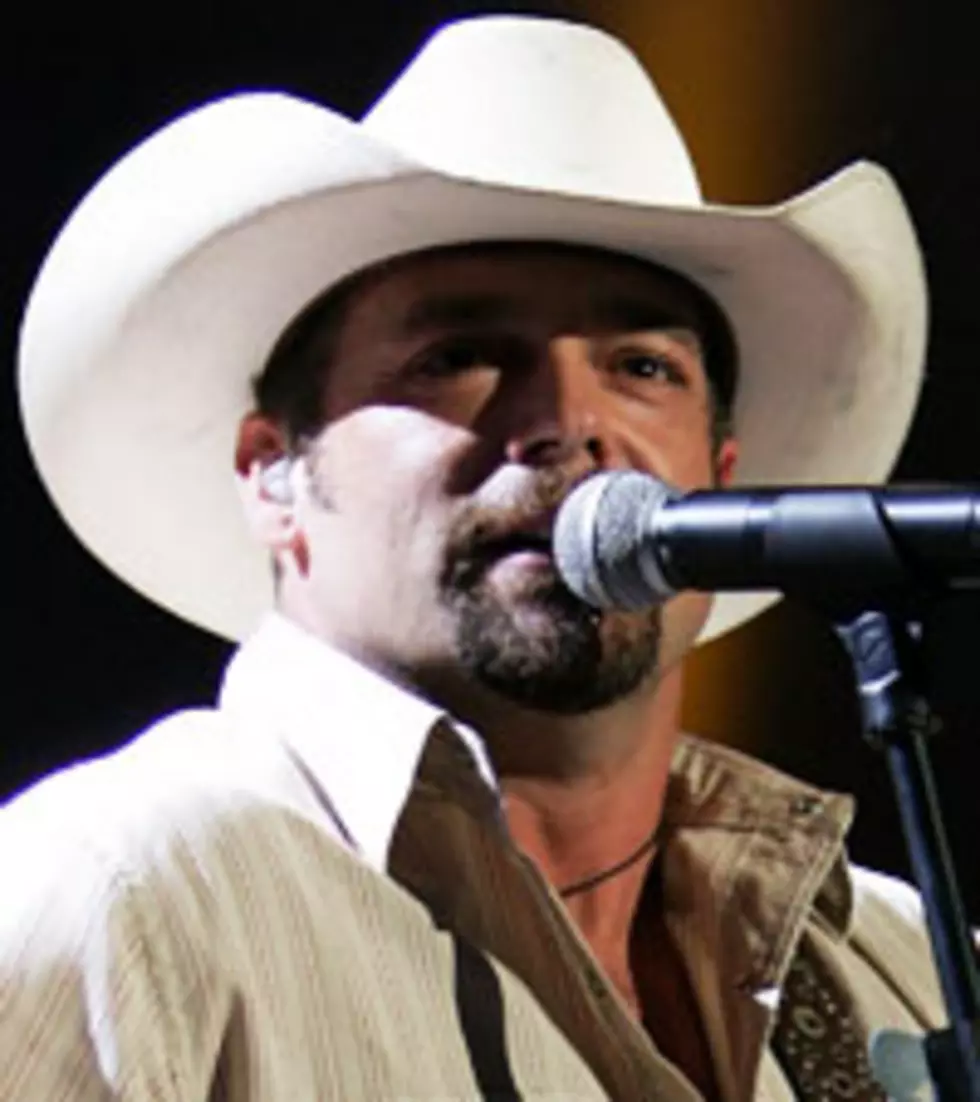

At first I was very gun-shy and I had a lot of trust issues. Slowly but surely these guys have done what they said they were gonna do, and that's let me make a record without anybody trying to influence what I sing, or saying, "we need a poppy-feeling song here, or Rascal Flatts is doing this, or Keith Urban is doing that" or whatever. I've always known who I am as an artist, but I've never really had an opportunity to show it except for my first record and now this project, to really make my record. Actually, when I first started coming back, I was so insecure and so nervous and so scared, because there's so much new, great talent out there. I thought, "Am I even gonna fit in this ballgame anymore?" But we played Mesa, Arizona, a couple of weeks ago and the place was packed. We did Temecula (Calif.) and there were 5,000 people there. Then we did Salt Lake City and had 6,500 people there. So it's been incredible!

Are you finding the crowds are mostly your loyal fan base from before, or is it a mix of new fans, too?

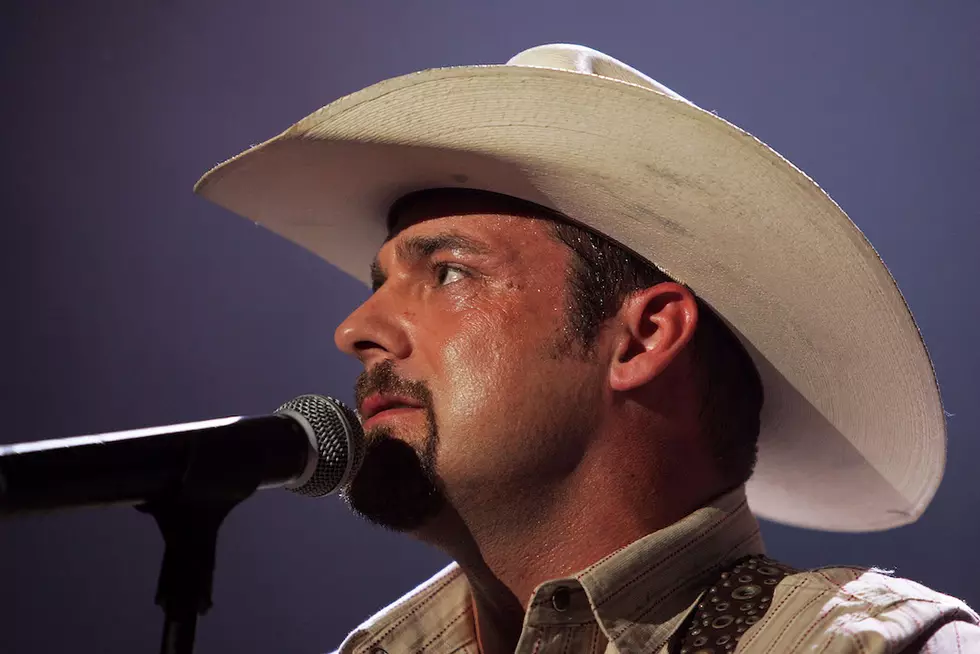

What's interesting is I've been asking people, "How many of y'all have never seen us," and the majority of the crowds have never seen us live. So we still have the Caglehead fans but I think they're bringing two or three friends who haven't seen me, and 60 to 70 percent of most crowds are new. That says a lot to me about the new single we've put out, "Got My Country On," and what it's done and how it's impacted. I don't know that I started it, but what I've been told through the town and people behind the music is I started a Southern rock-twang thing back with "On and On" and "Laredo." It was not the straight-ahead, traditional, Garth Brooks, Clint Black, George Strait sound. My goal always an artist is to create something that is uniform through every record but at the same time just gets better. That's one thing I think has been universal through my music -- when it comes on, I think people know before I ever open my mouth that's a Cagle song. But what I'm trying to do is broaden and make it better without necessarily making it different.

You penned a song on the album called "Dance Baby Dance," with the Warren Brothers, that's about the special bond between a father and a daughter. That song must have so much meaning for you now that you're a dad of three girls yourself.

Being a dad changed me in so many ways. When I saw Stella come out, her head was turned and she looked at me, and it was one of those things where when they put her in to measure her she was just hell-bent, get me out of here, wailing. I walked over and put my finger down in that little hand and she kind of exhaled this peaceful breath, and grabbed my hand, like "Oh, I'm safe." She'll never know how strong she is. That child, she made me want to be better at everything. Including being a human.

Your new single, "Let There Be Cowgirls," was inspired in part by your wife Kay's spirit. You said you when you saw her, you thought she was going to break your heart. Instead you ended up building a life with her. Does that amaze you, looking back on it?

She's a big part of everything in my life. It's funny because we both had that insecurity when we first met. There was instantly something between us, and the more we interacted I was thinking, "Man, this girl is really gonna do a number on me." At the same time, she was saying to herself, "This is finally gonna be the guy who just breaks my heart in half." I think the things she loves about me sometimes are the things she hates about me, too, though. Like one thing she loves about me is I give her the security she felt from her father, but some of the things she hates about me are the same things her father had trouble with. Her dad's not a soft talker, and when I snap off, I'm not a very soft talker either, but there are warning flashes that go off, "Hey I'm getting there." She's the same way. The thing that makes us work is both of us are willing to say, "Hey, this is my problem, this is the deal," and we work through it.

Another song, "Probably Just Time," talks about letting go of things that are beyond your control. Why did that particular song speak to you so much?

That song came from this: I had my kids, and I hadn't spoken to my mother in a long time. Because I'm the type of person where if you hurt me enough, I'll just flat cut you out, I don't care if you're mom, dad, Jesus. I don't care. I had my kids and I thought I owed it to my children and my mother to call her up and to tell her I would love to reintroduce you into my life, and forgive you of some things and have you forgive me of some things, and she declined seeing her grandkids at the time. So my wife made a statement, she said, "You know, it's probably just time for you let all of it go, honey." That was a song that when I heard it, it was one of the reasons that I called her. Because it was time for me to let go of a lot of baggage and a lot of things that I carried, a lot of guilt, a lot of hurt.

Do you feel like you've mellowed a bit and settled into yourself more than when you were younger?

Look, honestly, I know I've got a reputation for being a very hard person to work for. The people out there who are saying that are the people I've fired. But you can ask people who work for me. I have a talk, then I yell, I scream, pitch a fit and then I fire you. If those things don't work, it's like I don't know what else to say. I've gone from the nice guy, to the butthole, to "get the hell out." It's not easy. Now, instead of me fussing, I say, "Man, aren't we all grown men?" I've mellowed a lot. I don't know if it's age so much. I think it's a position of learning that I grew up having to fight for everything I've ever had. So the fight never ended. I had to learn that not everybody out there wants to get you. It's hard to learn that when you're a guy who makes the kind of money this industry can allow you to make and you've got everybody wanting in your pocket. I'm not trying to make excuses for my actions. What I am trying to do is own and be responsible for them and turn around and correct the things I've done wrong that didn't give me the result I wanted. My problem is I've never had the filter. I've never said to myself, "This is not the place for this." To me, it's like, "Yes it is, because right now I'm feeling it!" I've had to learn that. I allowed myself to get the best of me and paint a picture of me I didn't like in the past. I want to repaint the canvas. If it kills me and I have to swallow ego after ego and eat sh-- sandwich after sh-- sandwich, by the time this is over, when I leave this business, they're gonna say, "He made some good music, but man, he turned out to be one of the nicest guys." That's what I want.

More From TheBoot

![Chris Cagle Breaks Up Soldier Fight at Ft. Drum Concert [VIDEO]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2013/12/Chris-Cagle.jpg?w=980&q=75)