Why Did Bluegrass and Country Music Drift Apart? Here Are Three Theories

Concertgoers and tourists approaching the Ryman Auditorium from 5th Avenue are greeted by a statue and historic plaque celebrating the father of bluegrass, Bill Monroe. The Tennessee Historical Commission placed the marker, which identifies country music’s Mother Church as the birthplace of a now-separate genre, bluegrass, in 2006.

As the story goes, when Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, a band named for its home state of Kentucky, played the Grand Ole Opry stage in December 1945, crowd chants of “blue grass!” provided the name for a then-new hybrid of folk storytelling and string band precision. In the nearly 75 years since the commercial birth of bluegrass, it’s evolved from a new form of entertainment targeting country music audiences to a genre with its own history, traditions, awards and Billboard chart.

This split raises a pair of simple questions with three complex, overlapping answers: When did bluegrass and country music drift apart, and why do they remain separate genres?

Answer 1: Folk Revivalists Embraced Bluegrass

For one thing, in 1945, the Grand Ole Opry was a variety show with comedians, gospel singers and others as cast members of a program featuring way more than country stars Ernest Tubb and Eddy Arnold. A looser format allowed a genre to be created before audience members’ eyes — a happy accident that probably wouldn’t have happened in later decades. The Opry remained a haven for Monroe, his former band members Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and other early innovators of bluegrass until a different roots-friendly happening offered the genre a new home and a wider audience.

By the late ‘50s, the same folk revivalists behind the commercial rise of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and the rediscovery of such gospel and blues acts as the Staple Singers and Mississippi John Hurt fell in love with bluegrass. Soon, students on college campuses well outside of the Southeast praised Monroe, the Stanley Brothers and various other acts while providing a devoted, paying audience for Doc Watson, Hazel Dickens, Alice Gerrard and others. Through this lens, what we’d now call “hipsters” wanted to see bluegrass acts, allowing established names and up-and-comers to find bookings outside of country music circles.

The Stanley Brothers and the Osborne Brothers made history in 1960 when they played the first on-campus bluegrass concert at Antioch College in Ohio. Within a few years, the ongoing trend of bluegrass festivals began with a multi-day event hosted in 1965 in Fincastle, Va. From that point, bluegrass had its own live music infrastructure attracting country fans, folkies, hippies and others interested in traditional instrumentation, which allowed country music venues such as the Ryman to be tour stops and not home bases for an increasingly independent genre.

It’s hard to revisit the ‘60s without considering politics in the separation of country and bluegrass. However, there’s no obvious evidence that bluegrass’ shift from the conservative Opry to the liberal folk revival drove any sort of irreparable wedge between the genres (although it’s easy to assume that Earl Scruggs and Charlie Daniels, of all people, got plenty of sideways glances in Nashville after performing at the Nov. 16, 1969, Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam).

Answer 2: Country Music Went Uptown

As bluegrass carved its own niche with roots music fans, country music countered the popularity of rock ‘n’ roll in the ‘50s and ‘60s by favoring slick production and smooth-voiced crooners over its “hillbilly” roots.

By no means has bluegrass remained completely the same. Long before hippies and deadheads influenced “newgrass” in the 1970s, Monroe himself fine-tuned the sound of the Blue Grass Boys — a band that, at one point, included an accordion player. Still, every change in bluegrass at least maintains the fiddle, banjo and other stringed instruments that over the years went from necessities to novelties in country music. For past generations, it would’ve been unimaginable for Roy Acuff to lay down his fiddle for good, while nowadays it’s noteworthy when someone like Jon Pardi asks a bandmate or studio musician to rosin up their bow.

These different ways of embracing change lead up to a second argument as to why bluegrass and country split: Sprinkling hardcore bluegrass songs into playlists of increasingly electrified, rock-influenced and pop-friendly country singles sounded awkward to radio programmers and advertisers.

“It became big business, and it started to dictate what people are going to listen to,” bluegrass artist Rhonda Vincent reflects to The Boot. “Now, with the stations, they don’t want you to think that there’s a market for traditional country music because they want you to listen to what they want to dictate to you.

"To me, the music started being segregated as amplification came into play," she adds. "If you look back at the heyday when there wasn’t any amplification, every artist was on the same playing field.”

Answer 3: Bluegrass Stays Truer to Its Roots

Through this third and final lens, bluegrass split from the old-fashioned sound of country music during the folk revival, only for Nashville to earn a more cosmopolitan image over time while thrusting its old redneck baggage on its more traditional-minded cousins. When country music “went pop” in the ‘60s and dominated album sales and stadium tours in the ‘90s, the often-disparaged business got credit for more than pandering to rural, white stereotypes; when bluegrass received mainstream boosts over the years, however, it usually came through media that furthered hateful presuppositions about Southerners and made the genre look low-brow.

For example, the 1972 film Deliverance did two things: It aided the popularization of bluegrass in the ‘70s while terrifying people with biases against the South and next to no exposure to Georgia outside of Atlanta. In 2000, the harmless and fun O Brother, Where Art Thou? made some deserving roots, folk, country and bluegrass artists richer while reinforcing a limiting, cartoonish vision of old-time musicians.

“Flatt and Scruggs and Bill Monroe, our father of bluegrass, would dress up in a suit and a tie,” Vincent says. “They presented themselves in a very professional and sophisticated manner. Then you see the movie, [which] wants to portray it as toothless, bare feet and more in a hillbilly format.”

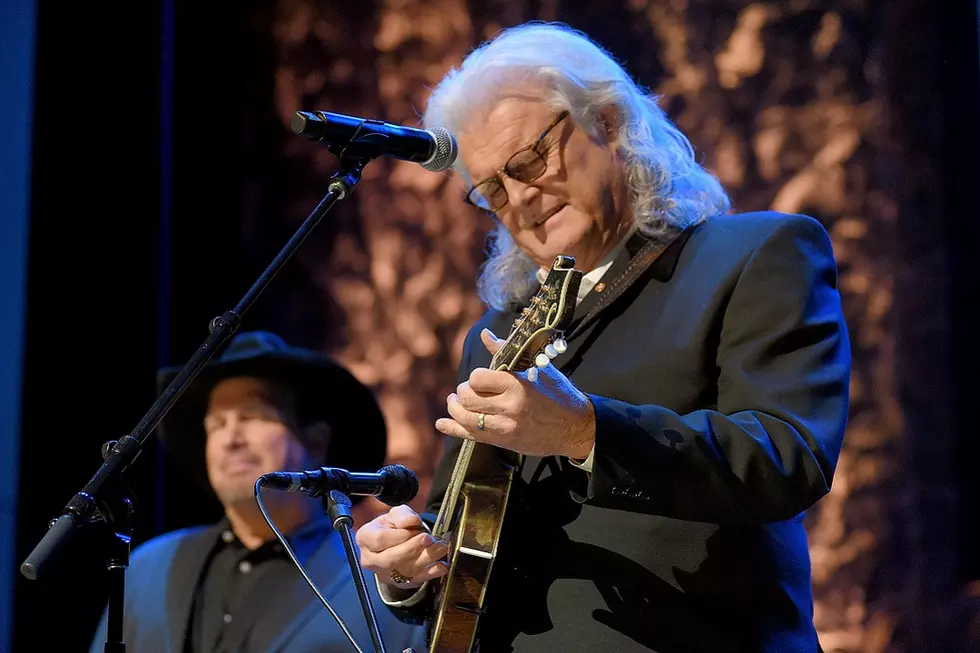

A lot has changed in Nashville since 1996, the cutoff year of Ken Burns’ Country Music docu-series. Most obviously, country music has become even more pop-accessible thanks to the rise of so-called “bro country” and the increased use of hip-hop beats. Conversely, bluegrass’ retro trajectory, and the rise of Americana music, changed when Monroe died on Sept. 9, 1996. Monroe’s passing inspired both Marty Stuart and Ricky Skaggs to stop chasing commercial success and become ambassadors for the music of their childhoods; Stuart kept things country with his vintage Telecaster in hand, while Skaggs unofficially became an elder statesman of traditional bluegrass music and culture.

In the years since ‘96, bluegrass has avoided growing stagnant by combining history celebrations with occasional flashes of musical innovation. More than 20 years later, Billy Strings, Molly Tuttle and others with deep bluegrass roots sound fresh while reflecting the legacy of Skaggs’ heroes. While behind-the-scenes players in country music race to keep up with popular trends, it's the bluegrass artists themselves who dictate slight changes to the music of Monroe and other influential pickers.

50 Country Songs Everyone Must Hear Before They Die

More From TheBoot