Radney Foster Interview: Revisiting ‘Del Rio, TX’ 20 Years Later

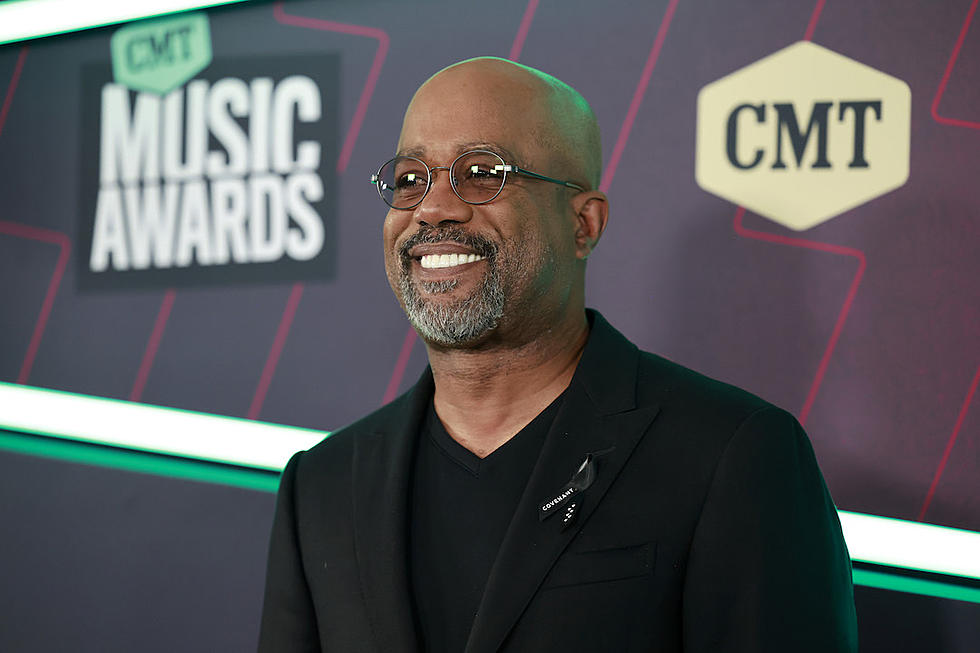

In 1992, after three successful studio albums and a handful of hits, country duo Foster & Lloyd (Radney Foster and Bill Lloyd), disbanded. The critically-acclaimed pair pursued solo careers but reunited in 2010 and released a new album together, It's Already Tomorrow, in 2011. Radney Foster, in the meantime, had written songs cut by several artists, including Keith Urban ("I'm In," "Raining on Sunday") and the Dixie Chicks ("Godspeed"). He'd also gained notoriety for the inspiration he provided to one Darius Rucker, the Hootie & the Blowfish frontman now enjoying a lucrative country career. So inspired was he, in fact, that Darius named his second solo album Charleston, SC 1966, an homage to Radney's solo debut, Del Rio TX 1959, with both album titles representing the birth places and years of their respective creators. With the 20th anniversary of his Del Rio album looming, and the frustrating predicament that the original CD was no longer available -- in spite of the fact that it contained a pair of Top 10 hits, "Nobody Wins" and "Just Call Me Lonesome" -- Radney set out to celebrate the collection's 20-year mark by re-recording it, this time as an acoustic album, Del Rio, TX 1959: Unplugged & Lonesome.

The Boot joined Radney in the cozy studio behind his Nashville home to talk about the joys and challenges of revisiting the songs that kick-started his solo career. He also shares the story of the new song on the album and the icons, both personal and professional, who inspired its title, and why he never thought anyone, let alone Keith Urban, would record what is now one of his best-known songs.

The original Del Rio album has been out-of-print for a while. Is that why you decided to re-record it?

I wanted to honor the 20th anniversary of it. It's not been available in print for years. Finally I was able to get them to at least put it up on iTunes, but that took a lot of arm-twisting. Every night, fans ask me where to get the songs or where to get that original album. An older fan will tell a younger fan, "you've got to get this record." A 22-year-old will download it right there. A lot of times, a new fan might know me because of producing Randy Rogers Band and songs they know from that, and he and his fraternity brothers come to see us and wonder what's the buzz, what's the show all about? For them, that first record doesn't exist. It was made around the time they were born. They'll say, "I know that 'Nobody Wins' song, I didn't know that was you." They'll say, "How do I get this song or that song" that I played that night. Well you can't, you can go on iTunes, that's the only way you can get it.

Were you concerned at all about re-recording the songs?

Every time I've ever heard someone go in and try to remake the original record exactly like it was, only now they own it, it's never ever met up to scratch. They always sound lackadaisical. You can't grab that lightning in a bottle twice. You could do a live record, or an unplugged version of it. Then, because of my friend Steve Fishell's MPI (Music Producer's Institute), I said, "Wait a minute, I can do both at the same time." So we had 20 students in the studio with us. We cut it in Austin at Cedar Creek Studios. But in doing that, I wanted to make sure that it had that immediacy of a live record. So I said no headphones. So the question becomes, the mandolin player says, "Can I fix my part?" No, because it's bleeding into my microphone and the vocal is bleeding into yours. So it was a very old-fashioned, old-school way of cutting the thing. Sometimes you get it home and you'd think, that would sound really good with a piano on it. So we would overdub that way, but not, "Oh, I hate that vocal can I sing it again?" Because that's not possible. It wasn't like they were walking in to do brand-new songs that you've never heard. Everybody got e-mailed a copy of Del Rio, Texas 1959. But there still is a lot of experimentation. You'd get in there and somebody would be playing something that wasn't on the original and you'd go, "Wait a minute, that's cool, play that again."

The album has even more of a Texas flavor than the original did. Was that something you were aware of while making it?

That was intentional. I wanted to use Texas musicians, I wanted to do it there and I wanted it to be unplugged. [Dixie Chicks fiddle player] Martie Maguire and [guitar player/singer] Jon Randall grew up playing in the Dallas area in bluegrass bands. Not together, but in the same little circuit as teenagers. They knew each other and they knew each other's playing very well. So that was sort of a homecoming for them and that really helped. Michael Ramos, who played keyboards on most of the things is a great, great session and sideman on a lot of rock things. He's played with John Mellencamp and all kinds of people. He brought a real honest Norteño and Conjunto accordion style to things, which is my favorite surprise on the record. In the second verse of "Just Call Me Lonesome," you go back to the border in about light-speed.

This album has a different running order and also has a bonus track, "Me and John R." on it. Why did you change the order?

I knew I wanted a bonus track, a lagniappe, if you will. The normal thing to do is to list the record off as it would've been the first time we recorded it and tag a bonus track on the end. We did that and it sucked. It just didn't work as a flow. Certain songs [on the new version] got slowed down. Like, "A Fine Line" is a real good example. That was kind of a rocker on the original. My co-producer, Justin Tocket, kept saying that it's an amazingly devastatingly lyric, and a cautionary tale. He said, "You need to let the lyric be the most important thing, and slow it down and be a storyteller. When we were recording, he would be like, "Slower ... slower." [laughs] Finally, I started finger-picking it rather than strumming. That's when it took on a life of its own. That's what made us rearrange the order.

How did "Me and John R." come about?

About two months before we were supposed to go in, I was writing with Darden Smith and Jon Randall. Jon Randall's name is Jon R. [his last name is Stewart], Johnny Cash, of course, is John R. My father was John R. From about the time my dad died, I thought, I need to write a song called "Me and John R." I always thought it would be something that I wrote about him or I would write it on my own, but it just never happened. Then I thought, here I am with Jon R. I told him that and he said that's what we should write today. We tried to get every John Cash reference we could into the song. But someone, somewhere along the way. said, "Me and John R. got nothing to lose." I said, "That's a double-edged sword." That could mean you have the freedom of starting over, starting a new life, or you could have nothing to lose because it's already been taken away from you. In the moment I got through writing that with them I was pretty sure it was going to go on the new record.

What do you think is the biggest difference between the original record and this one?

In the interim 20 years I learned that you're not selling perfection. You're selling an emotion, you're capturing an emotion in the studio. People don't buy music because it's technically great, well, some people do but I think most people buy music because it's emotionally great. So that's what you're trying to do. If it's a little out of time here, a little out of tune there, maybe that's part of the charm for people.

This was your first solo record. What do you remember about who you were at the time it came out?

For one thing, it was the first time I had recorded without Bill Lloyd. With Foster and Lloyd, we wrote some great songs but they were built around a band sound. That's different than being a song where you're just there naked with you and your acoustic guitar. So it really made me dig in and dig harder. That record is the culmination of me not only discovering myself as a songwriter but as a storyteller.

Now that you know the influence that you and that record in particular had on people like Darius Rucker, what is that like for you?

It's unbelievably flattering. People tell me how much influence that record had on them. It was flattering to hear Martie Maguire talk about wearing the cassette out when she was a kid. I love that. But you can't think about that stuff when you're going in to record. Especially if you're going to deconstruct it.

Lyrically, do you look back at the record and think you feel differently about certain songs, or relate to them in a different way?

Some of those songs were written from a personal perspective about a previous relationship [and] I don't have that relationship; I have a different one. And yet, "Easier Said Than Done," I feel the pain of because I know what it's like to have broken trust with someone. You don't necessarily have to have an affair to break trust. You can do it by promising you're going to get something done and not getting it done. It's not like you can just go back and say, "Oops, I'm sorry," and make it better. You've got to go repair that. You've got to work at it. That song really resonates with me as a cautionary tale, to this day. The songs were all written at a different time in my life and I'm still happy with those lyrics and I'm still happy with those melodies. But you can't help but bring some additional experience that's going to make you feel differently about them, emotionally.

What do you think about when another artist records one of your songs?

I like it when they make it their own. I really felt like a good example is Keith Urban's version of "I'm In." He didn't use the girl's background vocals. He made some of the hooks that were from the bass guitar on my version electric guitar hooks, so that he could play them. He really made the arrangement his own, and cleverly so. When you got somebody that's that talented, you go, "That's cool, that makes sense."

What's it like to sit in an audience and hear another artist doing a song you wrote?

It's pretty cool to hear 25,000 people in a basketball arena singing the words to your song! Keith got me up on stage in Dallas to sing "Raining on Sunday" with him. He introduced me, it was kind of neat. He said, "legendary Texas singer-songwriter Radney Foster" and the roof went off the place. It was very kind of him.

Have you ever had a song that you think, "I could never let somebody do the song because it's just too personal?"

Most of those I put on my record. And once it's on my record, I don't really have any choice, do I? Frankly, I didn't ever think anyone would ever record "Raining on Sunday" besides me. The second verse is about God, sex, mysticism, rain, deserts and all that stuff, and not necessarily in that order. You kind of go, that's way too weird. I'm the only guy that's ever gonna cut this thing. I was wrong. Happily so.

More From TheBoot