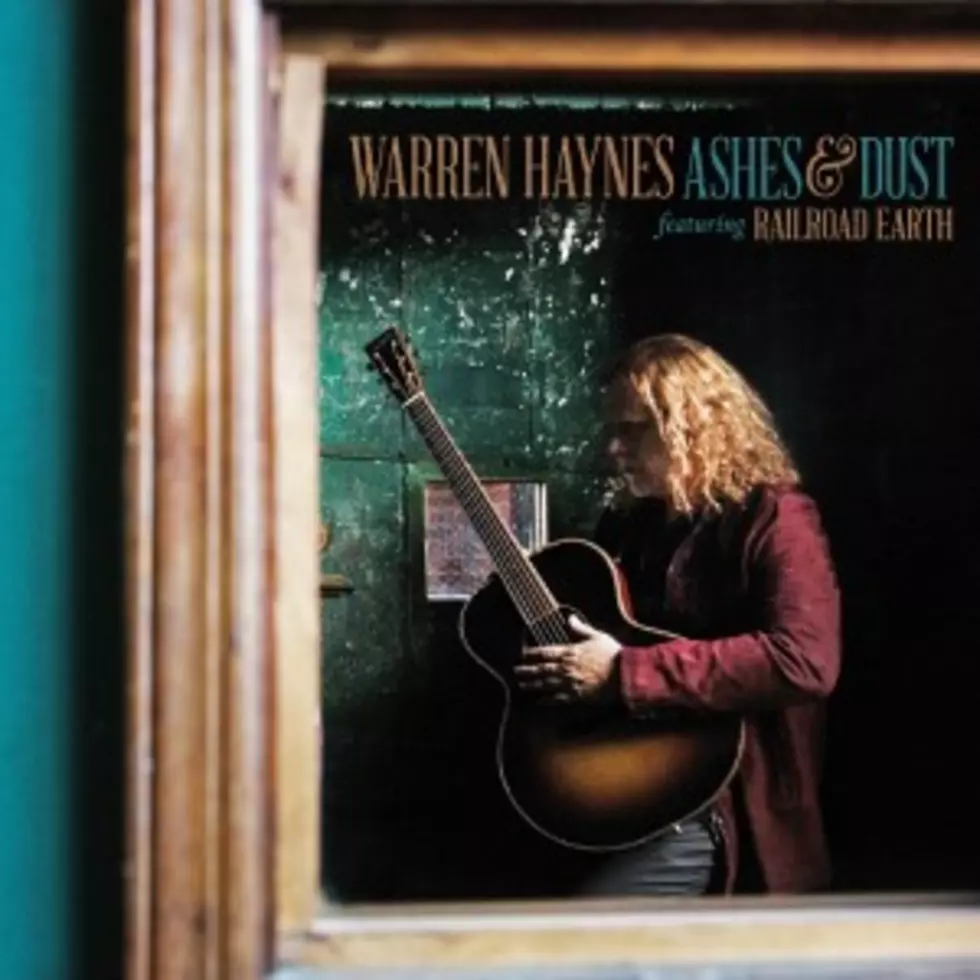

Interview: Warren Haynes Stretches His Americana Muscles With ‘Ashes & Dust’

Warren Haynes' name is well known among classic rock and jam band fans thanks to his work with with, among many others, the Allman Brothers and Gov't Mule, the latter of which he is a founding member. But the talented guitarist, singer and songwriter has also dabbled in other genres as a solo artist, including folk and Americana with his newest solo album, Ashes & Dust.

The 13-track album, which features Railroad Earth as Haynes' backing band and guest appearances from, among others, Grace Potter and Shawn Colvin, is set for release on July 24 and is available for pre-order on Amazon and iTunes, or through Haynes' website. Fans of Haynes' past work will no doubt be able to tell that it's him behind these tunes, but as he tells The Boot, the songs are more lyrically driven and allow him to exercise his musical muscles in a direction that doesn't necessarily fit his other projects.

Why did you feel as though this was the time to release an Americana project?

It could have been much sooner. I've been kind of threatening to make this record for probably seven years or so. I've been writing these kind of songs my entire life; I've probably written more songs in this direction than in any other direction. But these kind of songs don't tend to fit into the Allman Brothers or into Gov't Mule -- maybe a few here and there, but as far as overall, they tend to be departures from those kind of directions.

So I started thinking about making this record -- I was going to do a record with Levon Helm and Leon Russell and a bass player named [Tom] "T-Bone" Wolk -- this was probably seven years ago or so -- and T-Bone passed away [in 2010], and then Levon passed away [in 2012], and the whole thing just kind of disintegrated, so I turned around and made [2011's] Man in Motion, which was my last solo record, which was more like soul music meets blues, because I had accumulated a lot of songs in that direction as well, and they were both on my list of things to check off.

So since then, I've been writing more and more songs and going back through some of my old catalog and brushing off songs that I always wanted to record and never did, and it just seemed like I'd better get started, you know? I'd better start recording these songs.

We went into the studio and recorded 25 or 30 songs, so there's a follow-up in order as well.

So were you in the studio for a condensed amount of time, all at once, or was the process more spread out?

A little of both. We went in in November of last year and recorded for six or eight days and then took a break, and then came back and recorded for another week or so. But it was, again, a lot of material; it wasn't just all for this record. So while we were in the studio, things were flowing, and we were hitting it pretty hard -- long days, long weeks -- but I was able to take a break in the middle and kind of assess where we were, and that's always a good idea in the middle of a project.

How did you decide what made the final cut? When you were deciding, did you consider what might work best on this record vs. on the follow-up that you mentioned?

I was thinking mostly which songs would work together best for the first release, which ones belong together and also which ones were similar enough but different enough from each other to kind of make a cohesive statement. I still believe in the concept of an album, where every song should be part of an overall blanket statement, and so in some ways, I was looking at some of them thinking, "Well, this would be better for the next record," but I was mostly concentrating on this record and trying to get it to flow in a way that every song took you to a little bit of a different place, but it was all part of the same journey.

These songs represent personal memories and specific periods of my life and relationships, and I think, for the most part, it's a positive thought of living your life and moving forward and staying on the right path, but there's always going to be twists and turns.

I think you accomplished that. The album as a whole, to me, has this sadness running through it, but you also have songs that really stand out, sound-wise, from the rest, like "Stranded in Self Pity."

Well, I think any folk-influenced music is bound to have some sort of somber message. Sometimes the purpose of the actual music is to elevate the lyric in a way that you feel good about the message. I think these songs represent personal memories and specific periods of my life and relationships, and I think, for the most part, it's a positive thought of living your life and moving forward and staying on the right path, but there's always going to be twists and turns.

What made you decide to work with Railroad Earth on this project, rather than, say, assembling a band from scratch?

It kind of came about organically. We did a couple of things together, and they felt really good and natural, and I was looking for the right reason to take these songs into a certain direction, and for the right opportunity, and we played a few of them with that instrumentation and that chemistry that [Railroad Earth] have, and it just felt natural and felt right.

I knew at that time that that was the way the I wanted to make this record, and once we got into the studio -- I talked to them about this concept in advance, and they were all good with it -- I wanted to capture the songs with everyone hearing them for the first time. So I would play the guys a song, we would take the arrangement I had and change it or expand upon it, we would talk about what instrumentation might be nice, we would work up the arrangement and start recording, and when we felt like we had a good version of it, we'd move on to another song that they'd never heard before. And that's the way we did the entire process.

That's really cool! What do you think that lent to the final product?

There a sort of freshness and spontaneity that comes from the first time that people interpret a song, and I've always loved that. I've loved that in times when I was on that end of it and interpreting someone else's song for the first time, and interpreting my own songs for the first time, but in any situation where you're relying on improvisation and spontaneity, that first-take energy is always very special, and if you can capture it, it's, in some ways, the best option.

Is that how you generally record, or was this your first time trying it?

A lot of the Gov't Mule recordings are done that way. There might be a handful of songs that we've been playing live as a band before we go into the studio, but then there's always a handful that we really haven't played yet, and so we try to capture that fresh energy for those.

A lot of [Gov't Mule's] last record, [2013's] Shout, was done that way; some of the songs were actually written in the studio. And it's a great luxury if you can afford it, but you can't always depend on it because sometimes the magic's not there. We were lucky, in the case of Ashes & Dust, that the momentum maintained throughout, and we never hit a wall where we felt like we weren't being creative, but you do take that risk.

So how does that work with a song like the album's cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Gold Dust Woman" -- something that most people know and have heard before?

I'm glad you asked that. "Gold Dust Woman" was not a song we intended to do going in. It kind of got added to the program once we were in the studio, and it was one of several songs that I mentioned to the guys that I would like to record around midnight, when the day was finished. I wanted to get that feeling, that energy, that happens really late at night: musicians tend to play a different way, it's more relaxed, it's less cerebral, and that's kind of the feeling I wanted to capture with that.

And so, in the same way that we did "Hallelujah Boulevard," we did three takes of the song around midnight, and then we would come back the next day and listen and see what we had; we wouldn't even listen back that night. From there, we just picked the one that we liked and moved forward.

[For "Gold Dust Woman,"] Grace Potter actually came into the studio with me, and we sang side by side, like we like to do, and it was a really fun experience, and I felt like the version of "Gold Dust Woman" that we captured honored the original Fleetwood Mac version, but is quite different and has this kind of spooky, Celtic side to it that is a little unique.

There a sort of freshness and spontaneity that comes from the first time that people interpret a song, and I've always loved that ... That first-take energy is always very special, and if you can capture it, it's, in some ways, the best option.

And which is something I feel like Stevie Nicks might appreciate!

I hope so! Yeah, I would hope she would like it. I think it's quite a cool version.

It's funny that you mention "Hallelujah Boulevard" because that was also one that really stood out to me. It's so pretty and kind of haunting.

The song is a song I wrote a few years ago, and it's kind of questioning organized religion and the way a lot of traditional views, in that regard, tend to dictate the way our lives run, and watching at a distance how the world is dealing with that. And I wanted to, once again, capture that midnight feeling, and we did three takes of that song as well. Each one was quite different, especially the little psychedelic, surreal, sort of dreamscape jam that happens at the beginning of the song -- each of those was entirely improvised, and so we just chose the one that seemed to work the best. I think it was the third one, but I could be wrong.

But that was, again, just trying to go capture something in the moment, and that recording is completely live: the vocals, everything, is completely live on the floor.

When you're listening to this album, it has that Americana and folk feeling to it, but you can also very much tell that it's you. What's the difference, to you, between folk and Americana and what you usually do?

I guess one of the big differences is that these song are lyrically driven. They're more centered around the songs themselves, and whatever performance aspects we pursue are to enhance that and to expand upon that. In both the Allman Brothers and in Gov't Mule, the performance is equally, if not more, important than the composition because the bands are so ensconced in improvisation. And there's a lot of improvisation here, but it's more of a singer-songwriter record in the way that each song is a song that I wrote on an acoustic guitar, and I would sit around and perform it by myself and then think up ways to bring it to life with more instrumentation.

But you've also got "Spots of Time," which the Allman Brothers have played live for years, and "Glory Road," which you've also been playing live. What makes those two fit into this album?

"Spots of Time," I wrote with Phil Lesh from the Grateful Dead ... and we probably would have included it had we made another studio record, which we never did, so I decided to include it here because it never got recorded, and I invited Oteil Burbridge and Marc Quiñones from the Allman Brothers to help out with the recording. So that song has been played in a live context, but never by the guys in Railroad Earth, so we kind of took the onstage experience that myself and Oteil and Marc had, playing it with the Allman Brothers, and combined that with the freshness that the Railroad Earth guys had, having never heard it before. And I thought it made for a very cool, interesting take on the song.

"Glory Road," for the most part I only played as part of my solo acoustic performances, never with a band. The only exception was, I think when I toured with the Dead, we did it two or three times live -- and the Dead, you play a song tonight, and you may not play it for a month, you know? So it was nice to kind of bring it to life with all the instrumentation.

I'm a big fan of a lot of old-school country music ... Playing the Grand Ole Opry is such a legendary opportunity -- I mean, the opportunity to be part of something so legendary is quite amazing.

You made your Opry debut at the end of June. What was that like?

That was amazing! It was amazing. I'm a big fan of a lot of old-school country music. My dad is an enormous Grand Ole Opry fan, and I think it was more exciting for him than even it was for me. But it's such a legendary opportunity -- I mean, the opportunity to be part of something so legendary is quite amazing.

And I didn't think I was nervous until right before we went on stage, and I realized, "Wow, this is the Grand Ole Opry. A lot of legendary figures and lot of my heroes have been on that stage." But I thought we did good; I thought we had a nice performance. It's hard to wait in the wings and then do two songs and feel like you did your best, but it was cool.

Getting nervous -- is that something that usually happens before you perform?

I get anxious, in the way that I think athletes do before they play a sport or something. There's this nervous energy that I think is healthy, but I don't get extremely nervous, except in certain occasions that are high pressure -- and I've had a lot of experience in dealing with that as well -- but there are times.

I've been so fortunate that I've been able to meet and play with a lot of my heroes that I grew up listening to, and sometimes in those situations, you think, "Oh, I'll be fine," and then you might get a little tongue-tied or something. I've just been very fortunate to have those kind of experiences a lot.

More From TheBoot