Gerry House Interview: Country Radio Legend Talks New Book, Changes to the Business + More

Gerry House is one of the most beloved radio personalities in the history of country music.

For more than 25 years, House hosted 'Gerry House and the House Foundation,' a radio show that aired from Nashville each weekday and featured a mix of music, humor and interviews with some of country music's biggest stars. He has received an armload of awards for his radio career, including a spot in the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

In addition to his broadcasting career, House is a noted songwriter. He's written more than 50 songs for artists including Brad Paisley, LeAnn Rimes, George Strait, Reba McEntire, Randy Travis, Clint Black, Trace Adkins and more. His hits such as 'Little Rock,' 'On the Side of Angels,' 'The Big One' and 'The River and the Highway' have sold millions of records.

House has also written for a number of television shows, including the ACM Awards, the CMA Awards, the CMT Awards and 'American Idol.'

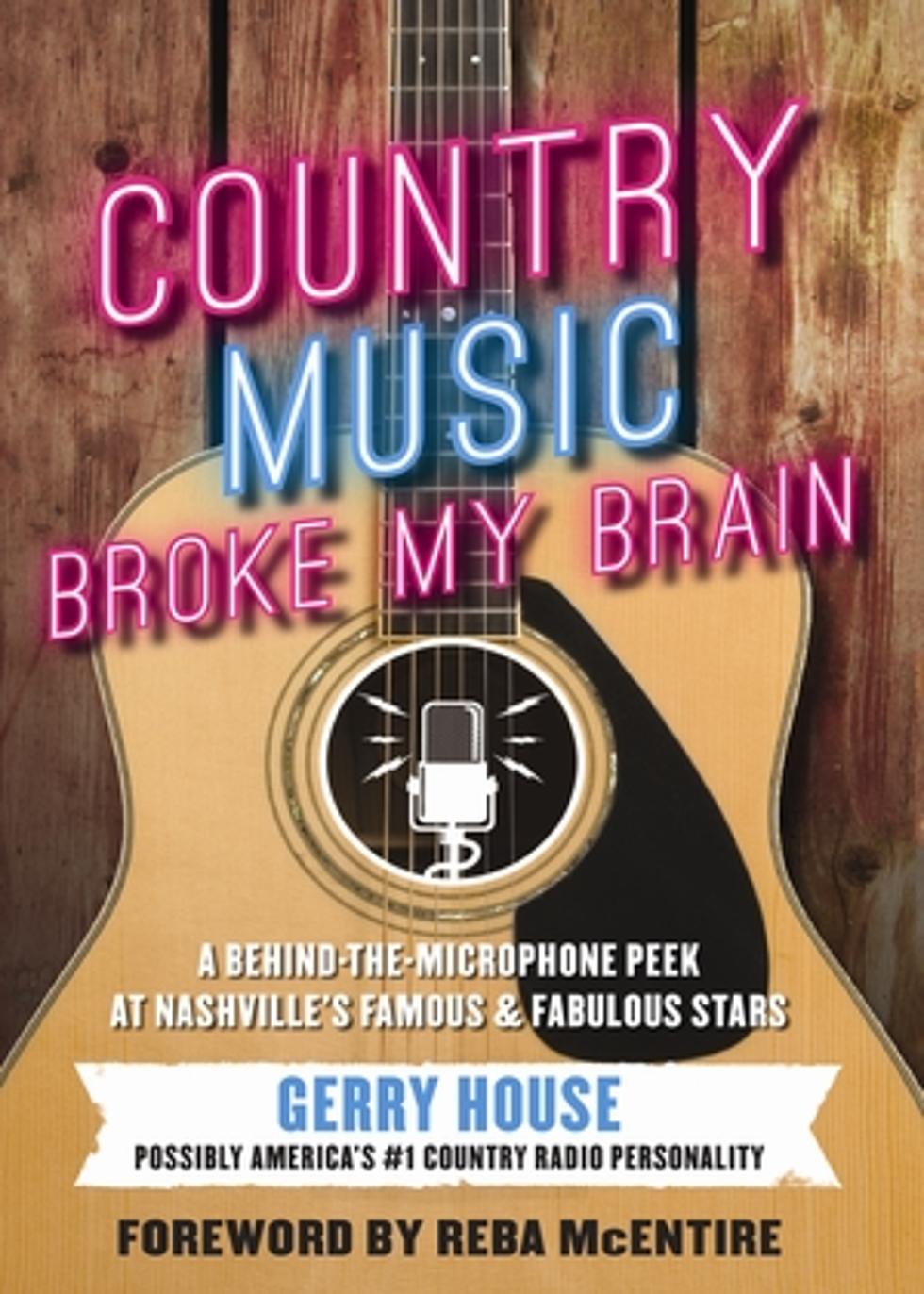

He has chronicled his one-of-a-kind career in a new book titled 'Country Music Broke My Brain,' which is set for release on Tuesday (March 4) via BenBella Books. More than just a chronology of his career, the book contains his hilarious observations about the craziness of the music business, including never-before-published conversations with such legends as Reba McEntire and Johnny Cash.

The Boot caught up with House recently to discuss the book, his legendary career, the changes that have come to the music business and much more in the following wide-ranging interview.

I really enjoyed your book. It's humorous, but it's also a real insider's look at the business.

Yeah, there's a lot going on there. People tell me it's not what they expected. They expected it to be a radio-based story, and it's not at all. It's a little bit about my career, but it's mostly about things that I've seen and done over the years.

There are a lot of insider stories in the book. How did you decide what you wanted to tell and what you didn't want to tell about various artists and various situations?

I was lucky, because I was on the radio. So I had kind of a guide to what I could get away with and what I couldn't get away with. If I wouldn't say it on the radio in public, I didn't want to say it in the book in public, either.

There's some things you know -- personal things about my friends that they wouldn't want to talk about. Family problems, or just stuff that comes up in day-to-day life that's nobody's business. So I would leave all that stuff out. So I was pretty lucky; I kinda had a 30-year guide of experience of living like that.

Your show was always one of the high points of everyone's day in Nashville. If you had to commute, you could get in the car and just laugh all the way.

[Laughs.] Well, that's so kind.

What was great about it was it was so spontaneous. You could say some stuff sometimes that I didn't think somebody could get away with on country radio. People just liked you well enough to let you get away with maybe ribbing people a little bit, in a way they weren't expecting.

Yeah, we had a pretty open and honest conversation. I had great people working with me, so I was able to -- we really just entertained ourselves, and whoever just happened to come in on the show just kinda joined in on whatever we were talking about. I would rarely spend a lot of time talking about their latest project, as much as I would just, what's going on in a famous person's life, whether it was Johnny Cash, or whether it was Hunter Hayes.

The microphone is kinda the great equalizer, in some ways.

Radio is great. The thing about radio is that it's such an immediate medium. It's really the last entertainment place where the public can immediately react and call you if they like something, or they don't like something. There's no other medium that's like that. Newspapers and magazines, and maybe even websites you can get feedback, but broadcast stuff -- television and movies, you're always removed. I've done all that, and I like the immediacy of radio.

I mean, not always. [Laughs.] Sometimes people could call and tell you how bad it was. But it's really honest.

Can you think of any instance in which you had a guest on the air that people just started calling in and objecting to the guest, or something they'd said?

I can't think of anybody. I mean, I've had guests that wouldn't talk. I've had guests who were hungover. I've had guests who were sick. But I don't believe I've ever had a guest where the public didn't like them enough to call.

I've had a few people fire off some stuff. I think Natalie Maines could be kinda testy when she came in. But she's actually a nice person. She's actually sweet. She's just very political, and you know how she had her issues with the country music audience, and with Reba. I was kind of in the middle of all of that. But she's actually an adorable human being.

Is it fair to say that she's way too opinionated for the genre, and holds opinions that just don't match up with those of the audience?

Yeah, I think [the Dixie Chicks] could have survived. I think they could have been okay, if they hadn't sort of fired back so harshly. But they were upset, and I understand that. I mean, they did not say anything about the troops, and I make a point of saying that in the book. They kinda got mixed up in, "We don't support the troops." I don't know anybody who doesn't support the troops.

But it's a very patriotic audience, it's a very armed forces-oriented audience, and a lot of the artists just do amazing things for guys who come home without legs and stuff. It was so emotional, too, when they said what they did, but they kinda got caught in a crossfire, and that was the end of it.

Natalie was the spark plug of that whole outfit, and was a great singer, and I want to make clear, I didn't have any issue with her at all. It was just a raw time; people were scared, and angry, and upset. We're going into war. There was a lot going on.

Radio has changed enormously since the early days of your career. Did any of those changes -- for instance, the centralization of playlists -- play into your decision to end the show?

Not really. For me, I was the last -- when dinosaurs walked the Earth, I went on the air. I could play pretty much whatever I wanted, and I did. I played a pretty wide range of music, and new music, and songs that I liked. I was able to do that. I really didn't get any corporate pressure at all not to do that.

I think the centralization thing is kind of overblown. I mean, corporate radio, they're just trying to find the hits, like everybody else. They're trying to appeal to the widest audience. It's not like they're not playing something on purpose.

Some people's objection is that they feel it maybe homogenizes things, maybe causes a little bit more of a decision to play stuff that reminds the audience of a thing that just succeeded, which causes everything to be more alike.

Yeah, that's just a trend. But that's been going on . . . it's funny, I ran into Paul Simon in Vegas, and I was talking to him. I used to be on XM, and he knew I was on XM, and I said, "What are you listening to now?" And he said, "I listen to Willie." Which is the channel that plays all that classic stuff from the '50s and '60s. And he goes,"They're great songs, but all of those songs are exactly alike." [Laughs.] And they are. They're all just the same chord changes, and it's all about lyin' and cheatin' and drinkin'. So that was going on, that same kind of homogenization was going on fifty years ago.

It's a terrible, awful, superficial business. But that's showbiz! If you've been hit with an ugly stick, I'm sorry. When that happens, then you go into radio, like I did.

That's true, when you put it that way. Like the Nashville Sound -- all of those records have the same essential elements.

Well, yeah. Same players, in many cases the same background singers, the same producers. You know, Nashville's a factory town. It's a little community. It's opened its doors to outsiders a lot more in the past ten years than it ever did before, but you're gonna get the same kinda stuff when it's written by the same 15 or 20 songwriters, and the same players. It's gonna sound alike.

It seems like the artists have gotten better looking as time goes on, and some people argue that with vocal tuning now being available, that it affords people who can't sing that well a career, if they're good-looking. What's your take on that?

Look, it's showbiz, and there are people who are hideous who have fabulous voices. And that's brutal honesty. I think if your choice is to have somebody who's relatively presentable, or have a guy that girls are gonna scream for . . . I mean, that's part of the marketing. That's part of the package.

My friend Keith [Urban] is on 'American Idol,' and I can see them struggle with somebody that's a fabulous singer, but they go, "Is this really the American Idol? Is this really . . .?"

I mean, it's a terrible, awful, superficial business. But that's showbiz! [Laughs.] If you've been hit with an ugly stick, I'm sorry. When that happens, then you go into radio, like I did. [Laughs.]

One really funny part of your book, you hosted a reality singing competition called 'You Can Be a Star' before they were such a big thing. What do you think of the absolute glut of shows like that now?

I think it's just another factor of the business. I find that the people on 'Idol,' I can't tell you who the American Idol was two years ago. I have no idea.

When they first came out, I think the novelty of it and the excitement of it was amazing. Kelly Clarkson is a friend of mine, and is just an ungodly, unholy singer. She's just great. And I think there are people who followed in her footsteps who weren't quite as magical.

It still comes down to having hit songs and everything, and having stage presence.

It's funny, when we would watch the show over the years, I would think, 'That person who finished fourth, they'll be coming to Nashville, and I'll see them on my show in about six weeks.' And sure enough, there they would be. I can't remember -- Josh Gracin, I think was the guy's name. He was a Marine, and he had a deal, and it's always those third or fourth-level artists who don't win 'American Idol' who are interested in country, and they've kinda got a leg up and a little bit of fame, and next thing you know, they're coming in with their record. Which is fine.

When I was a little bitty kid, Ted Mack's Amateur Hour had gone off the air, but I was aware of it. Amateur shows have been going on since the '30s. This is not something new.

Frank Sinatra won one of those, if I'm recalling correctly.

Yeah, he did. I wasn't around then, believe it or not. [Laughs.]

You devoted so much of your life to the show. When it came to an end, did you think, 'How am I going to fill up all this time?'

I wondered about that. Of course, I wrote the book, I started after I got off the air, and it took me about a year. But I do a lot of other things besides the radio show, and I always have. I'm a songwriter, and I'm writing television shows, and writing for acts, and writing for other radio shows. I'm basically a writer. So I had plenty to do, and still do. Some days I think I wouldn't have time to do the radio show now. And I get to play golf.

And the greatest thing in the world is getting to get up with Allyson House and have breakfast, which I didn't do for 35 years. I never did that. I got up at 3:40, I was in the studio at 5AM. I just was never home. A lot of times I would go to work in the dark and come home in the dark.

Songwriters are not the enemy. But they've been turned into these greedy, money-hungry people who just want to be paid. Well, they just want to be paid! Like they have been getting paid. I don't know why that's so tough for people to understand.

You've been in songwriting for a long time as well. The changes that the internet has brought to the business -- with downloading, and everything moving to a single-song focus -- how has that changed the game for a songwriter?

Well, the whole industry's just been decimated by -- it started with Napster, and it's gone on to where now, people just expect music to be free. People don't want to pay for it. They don't want to pay for the use of it.

I read a great article in the Wall Street Journal by one of my songwriting heroes, Burt Bacharach, and he cited an example of the girl who wrote 'Beautiful' for Christina Aguilera. Pandora played that song 12 million times, and paid the songwriter $349.

Well, that's absurd. It's all these companies who are saying to Wall Street, "We're worth 2.2 billion." But then when they go to have to pay, they say, "We're just a start-up, and we're not making any money." And it's absolutely killed the PROs [performing rights organizations], and it's hurt songwriters, it's hurt record companies. People just get it for free.

People just don't understand intellectual property. They don't understand that I created it, I wrote it, I own it. It's infuriating to have someone say, "No you don't. I'm going to use it all I want, and I'm not going to pay you for it." There's no other industry like that.

The problem is, they don't see it as theft.

No, they think all songwriters are rich, and they get really sarcastic: "Oh, boo hoo, I'm sorry Bruce Springsteen isn't getting another million dollars." But that's not the point. The point is, this is my creation. It's just as if you were a carpenter, and you put up a nice new porch, and somebody comes along and says, "Hey, thanks, but I'm not going to pay you for it, because it's on my house, and I'm not going to pay you." It would be infuriating.

Is there any way around this that you can see? What will it take for this to change?

I don't know. I don't know how they get their hands around it now. I think there's wiser people than me still fighting it, and thank goodness, because you can't just shrug your shoulders and say, "Well, the genie's out of the bottle." Which is kind of what the people who are stealing it and using it for nothing say. And they always blame the record companies, the greedy record companies. Well, you know, it's a business! They're trying to make as money as they can. It's not greedy at all.

What if they were? Does that mean you don't have to pay?

Yeah! And it's not like it's necessary to live. If you don't want to pay for it, don't use it. Don't buy it. And now they're getting around that, even. They're getting around it where you can't deny somebody using it. Spotify and Pandora and those people are going to say, "We're going to use it, and we're going to pay you what we want." That's what it's coming down to. That's why they're in court right now. And God bless BMI and ASCAP for suing those people.

If that doesn't get solved, there won't be any publishing deals -- look at the next generation of songwriters coming up. What are you going to be able to pay somebody when they come to town and want to write songs, if there's no revenue?

That's right. Exactly. Songwriters are not the enemy. But they've been turned into these greedy, money-hungry people who just want to be paid. Well, they just want to be paid! Like they have been getting paid. I don't know why that's so tough for people to understand. It's infuriating.

You talked a minute ago about some of what you've got going on. What are your future plans outside of this book?

I have a TV pilot that I've written, and I have friends that are actors and actresses that are in the business. And you can probably figure out who they are; they do a lot of television. And I would like to write for them.

I'm working on the TV pilot, I'm writing, I've started two new books, I'm in the middle of about 15 songs in some form or another, and I'm writing for a couple of internet TV shows, and I've been offered another job writing for another radio show. And I've been offered a couple of radio shows, but I don't think I'm going to go back to doing that. I kinda did that, and I'm done.

More From TheBoot